As ever, we’re here for you in advance of ICANN80 in Kigali, Rwanda, with some updated TACO stats to get everyone in the mood.

Our focus for this post is: where do Law Enforcement disclosure requests actually come from? This question was recently raised in the ICANN Registration Data Request Service Standing Committee by a committee member who requested that ICANN track and publish this information.

Looking at which countries’ law enforcement representatives are interested in accessing previously-public Whois data can provide us with interesting information about the necessity of such information for law enforcement efforts both at home and abroad. Some of the strongest advocates of the RDRS are law enforcement, so it is useful to see if those who advocated for it are actively using it. In the long run, this data may also provide a better understanding of who wants—and who gets—the private data of citizens around the world.

Tucows has been gathering law enforcement requestor location data since we started operating our TACO platform in 2018, and we hope that the information we provide will serve as an amuse-bouche while we all wait for ICANN to provide the main course.

Law Enforcement disclosure requests by location

Tucows divides law enforcement agencies (LEA) into two broad categories: “local”—for the countries where we have offices: Canada, Denmark, Germany, and the United States—and “foreign”—for LEA from all other countries.

All disclosure requests, including those from LEA, are reviewed by Tucows for legitimacy; we have recently noted—and been alerted to by our LEA partners—an increasing rate of attempts to pose as law enforcement in order to gain access to information or disrupt DNS services. We work hard to protect the data we hold, and our customers, against this type of threat. Doing so involves maintaining relationships with local law enforcement who can help us authenticate requests.

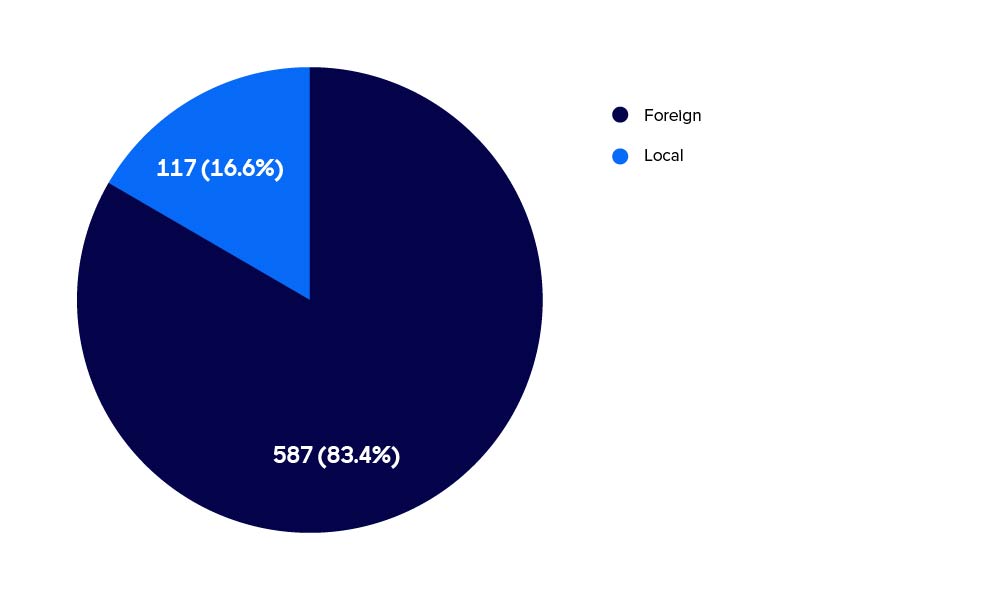

The vast majority of LEA requests Tucows has received since we started TACO were submitted by foreign law enforcement.

LEA Request origin (local vs. foreign)

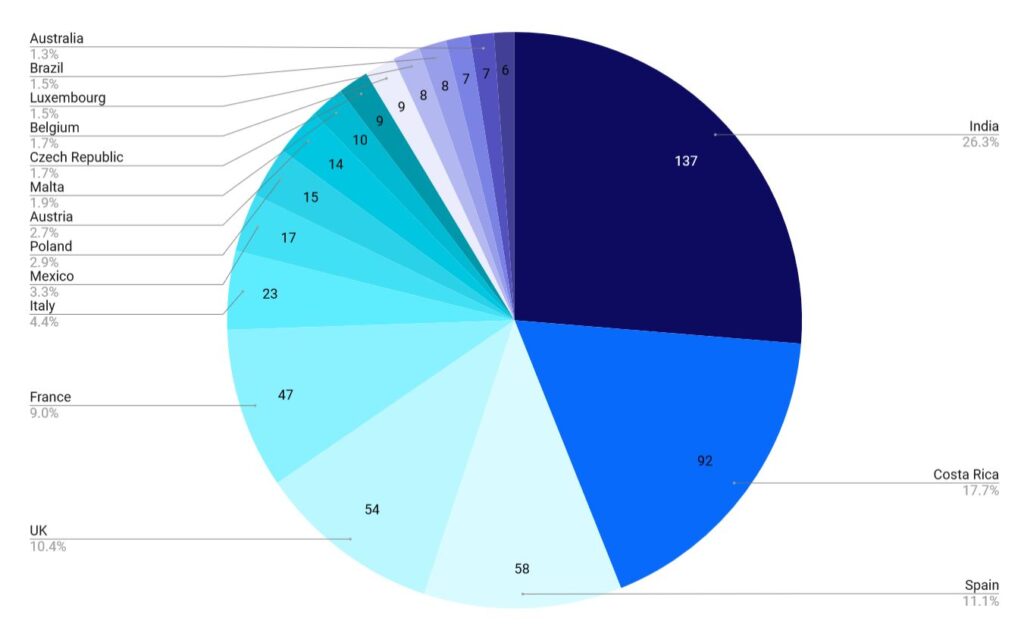

This is not surprising since the Internet is global, and Tucows only considers four jurisdictions to be “local.” The chart below shows the locations of foreign law enforcement (down to 1.5%—the remaining countries are listed below the chart in order).

Foreign LEA request origin

Countries not shown in chart above: Greece: 1.23%, Australia: 1.23%, Japan: 1.06%, Russia: 0.88%, Netherlands: 0.70%

That the UK ranks highly comes as no surprise, as certain of the UK’s law enforcement agencies have a mandate to combat Internet-based threats. We work closely with the City of London Police as well as the National Crime Agency to ensure that we get them the data they need within the standard parameters of working with foreign law enforcement (due process, due process, due process!).

Costa Rica’s position may surprise some, but the Costa Rican police discovered early on how to submit high-quality requests for previously-public Whois data and have one of our oldest TACO accounts. Tucows is pleased to be able to help them in their efforts to combat Internet-based fraud that targets Costa Ricans.

India’s position on the list, however, surprised even us. Indian LEA requests include a significant amount of alleged intellectual property infringement, suspected fraud, and pornography (which is illegal in India). They do not, however, have a good track record of submitting requests that allow us to release data (just under 18% of India LEA’s unique domain name requests resulted in release of data).

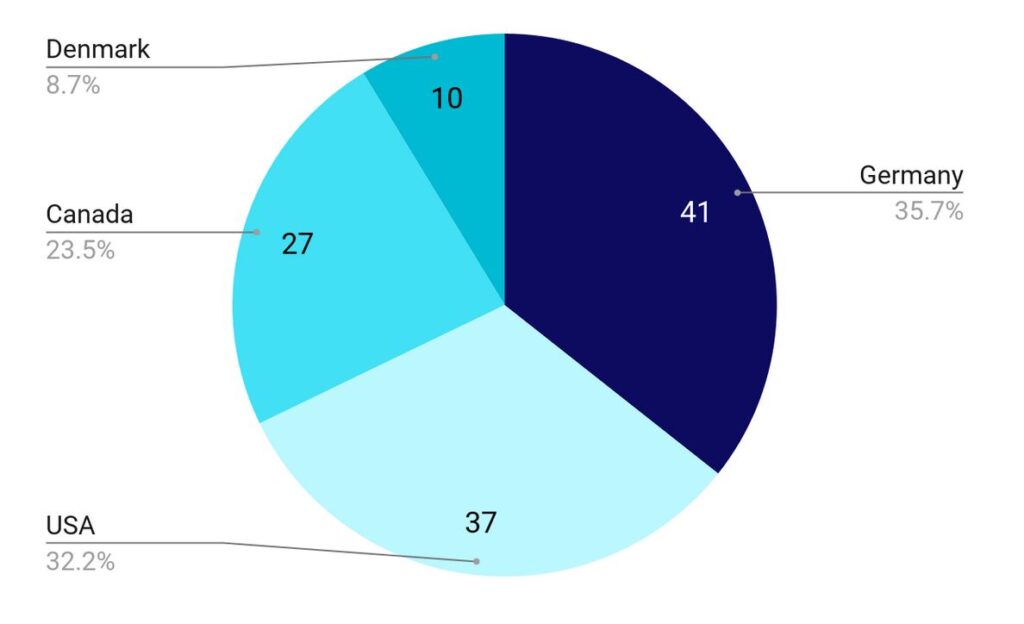

Local LEA request origin

When we compare local LEA to everyone else, Germany, the US, Canada, and Denmark are the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 13th (respectively) in terms of frequency of request. What this tells us is that foreign law enforcement is far more interested in our registrant data than are local law enforcement—although at ICANN, it is often US LEA that argues most fiercely about needing such access.

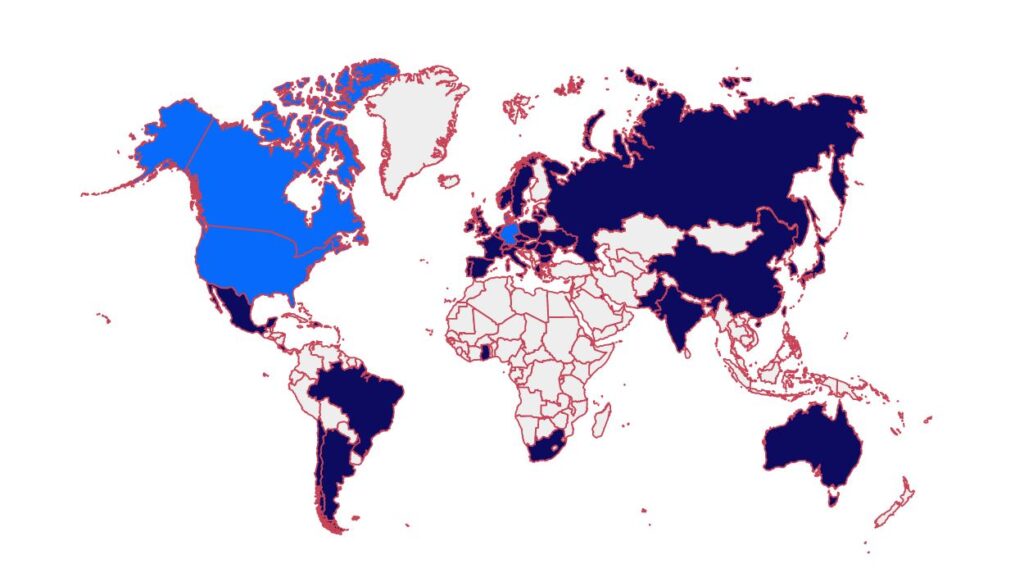

World map of all LEA requests

Law Enforcement disclosure requests with outcomes

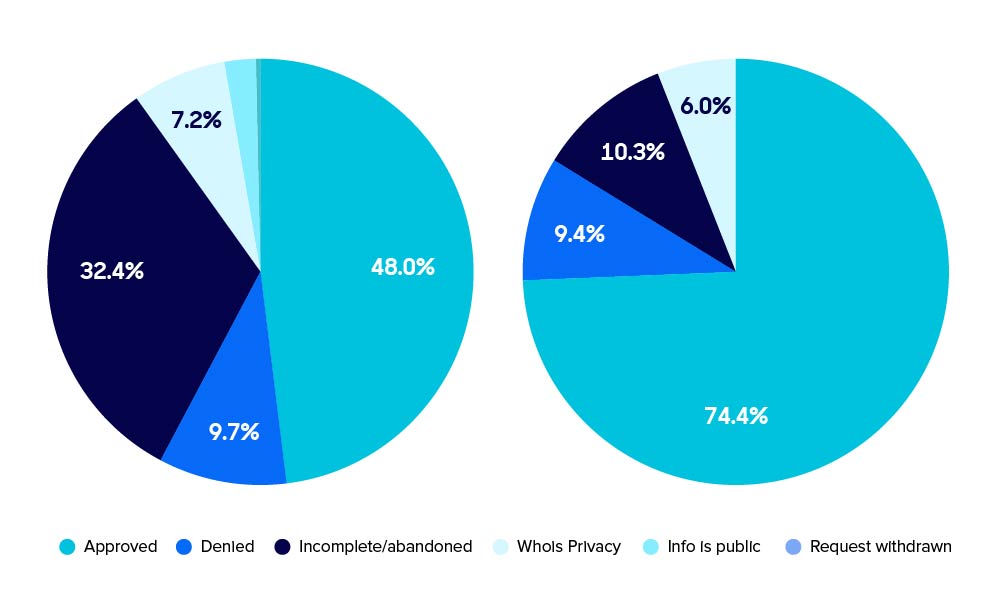

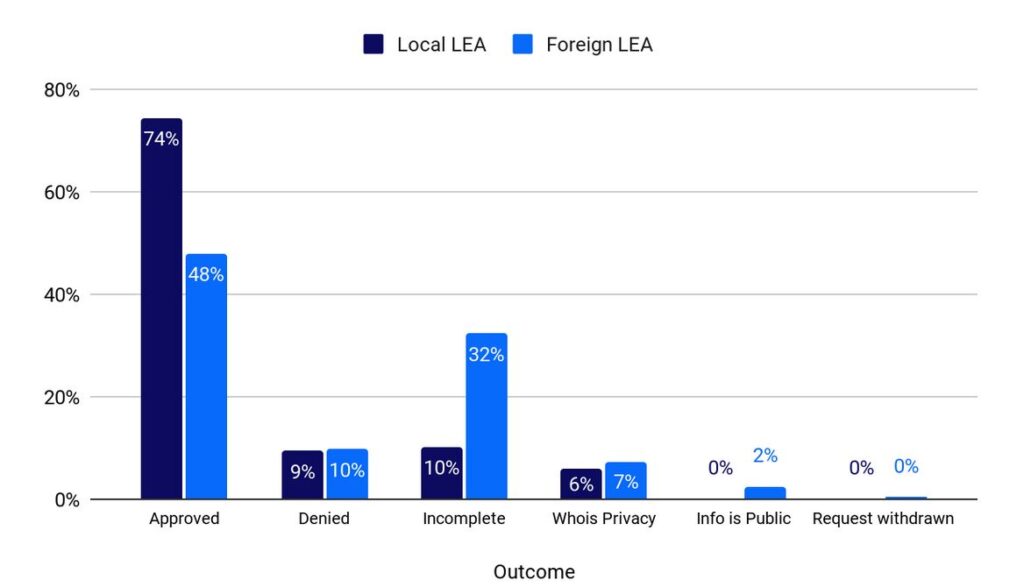

Perhaps more interesting than just the location of requestors is the location of requestors compared against approval rates. Local LEA is about 25% more likely to be approved for access than are foreign LEA. In addition, foreign LEA are far more likely to abandon requests. The denial rate is about the same for both.

Foreign (left) and local (right) LEA request outcomes

Tucows requires that each foreign LEA requestor provide answers to the RrSG-recommended Minimum Required Information for a Whois Data Request. This allows us to adequately assess the requestor’s need and balance it against the rights and freedoms of the data subject, keeping in mind the potential concerns of releasing information to a foreign government entity.

Local law enforcement is treated differently; their requests are still evaluated, but we use the local requirements of cooperation and due process (different for each country) to evaluate their requests since we are familiar with them. It is, therefore, no surprise that local law enforcement is more likely to have their requests approved.

Below is the same information presented differently, in case that is more helpful.

LEA request outcomes

Another data point of interest is the location of the most successful requestors. Below is a chart showing success rates. To clean up the data and ensure statistical significance, we did not include rates for any jurisdiction that requested information for fewer than 10 domain names. We include below only foreign jurisdictions with a success rate of at least 70%, and each of our local jurisdictions, to see how they rank.

| Location | % Approved |

|---|---|

| Germany | 93% |

| Denmark | 91% |

| Costa Rica | 86% |

| Canada | 71% |

| Belgium | 70% |

| USA | 50% |

Germany’s high success rate can be attributed to a unique local law that requires our cooperation so long as the request demands information that we hold and the requestor indicates the specific law that was alleged to have been broken. We have only denied one German request—in that case, they did not provide the broken law they were investigating.

We addressed above why Costa Rica is so successful: they request only in circumstances where the need is clear and clearly laid out to us in the request.

Locally, Canada also ranks quite highly, which we attribute to our close relationship with the various agencies making requests and to being able to tell them quickly when we may not have information that will be useful. This often includes helping them understand whom they should go to for additional information.

When it comes to local law enforcement, the US is running at about a 50% success rate. While we have relationships with members of national law enforcement entities, we do not have relationships with every single one of the tens of thousands of law enforcement entities in the United States. Whenever we receive a request, we do our best to reach out and explain to them what we need, and why, so that we can help them as best we can in their investigations.

On confidentiality

It’s also important for us to address the issue of “confidential” requests. In every jurisdiction, there is a provision for obtaining information about a person without alerting them to the request—this is allowable in certain circumstances under due process. It also, however, often requires extra steps: the requesting law enforcement officer must convince a magistrate that secrecy is necessary, and sometimes the magistrate will impose requirements about how quickly charges must be brought, putting a time limit on that secrecy.

We built functionality into TACO to notify data subjects that their data were disclosed—and to whom. This disclosure is automatic and simultaneous with the access of the data. For local law enforcement, we allow them to keep part of their request for previously-public Whois data secret: the data subject will still get a notification that their information was accessed—just not by whom. We consider that this is a reasonable balance between the rights of the data subject and the requirements of an ongoing investigation. For even more secrecy—no notification of the disclosure to the registrant or, sometimes, to the reseller—we require a sealed warrant.

We do not allow foreign law enforcement to submit confidential requests. However, for all law enforcement entities, we only disclose the law enforcement agency and address, rather than the agent’s direct contact information. For example, a request from Jane Smith of the National Crime Agency in the UK would have only “National Crime Agency” and a mailing address or public phone number disclosed to the data subject, rather than Officer Smith’s full name, email address, and direct line. Again, we believe that this is a reasonable balance between the rights of the data subject and the requirements of an ongoing foreign investigation.

We hope that the above provides some interesting and useful context for requests made by law enforcement through the Tucows TACO system (or of Tucows through ICANN’s RDRS system). We look forward to comparing our numbers against ICANN’s RDRS metrics for the law enforcement request landscape in the broader community.

As ever, if you have questions about specific numbers we didn’t include, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

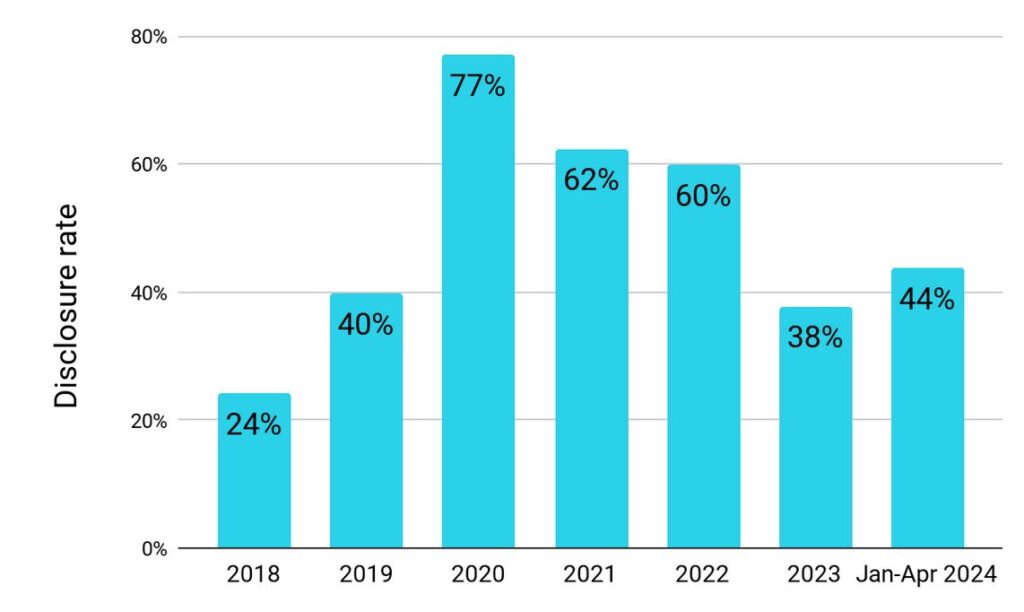

Tiered Access Statistics: 1 January – 30 April 2024

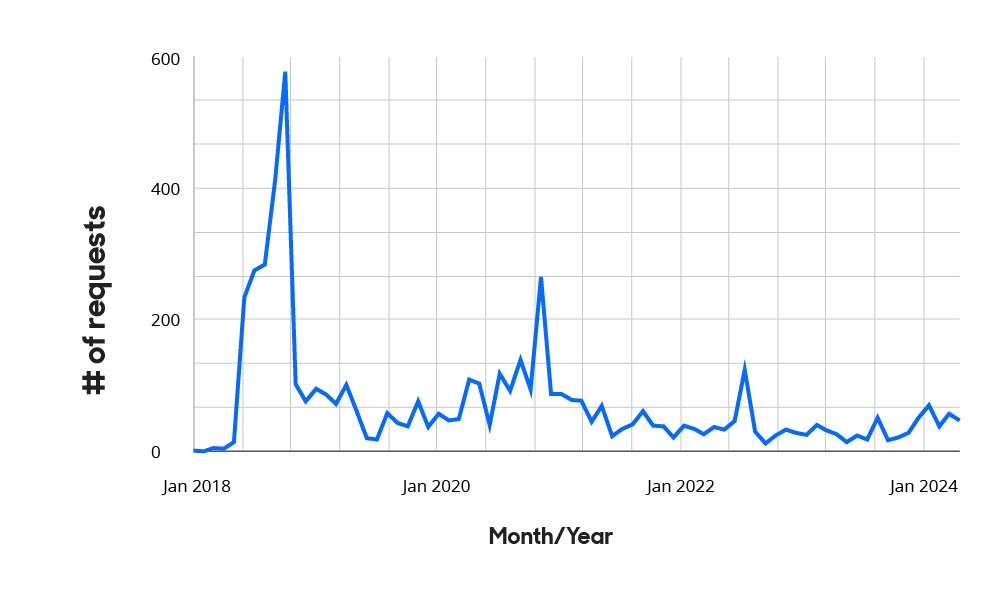

The new period covers January through April 2024. We received 224 requests in this period, bringing the total since we began tracking it up to 5762.

Of those 224 requests, 131 (58%) came in through the RDRS, while the remaining 93 were submitted to us directly.

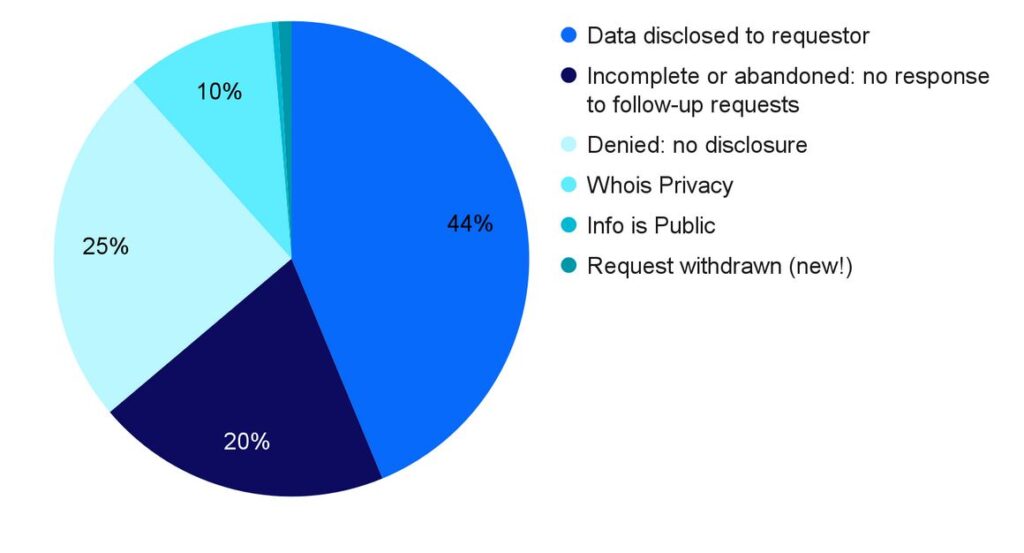

Data disclosure request outcomes: New Period (January – April 2024)

This includes requests submitted via both TACO and ICANN’s RDRS platform.

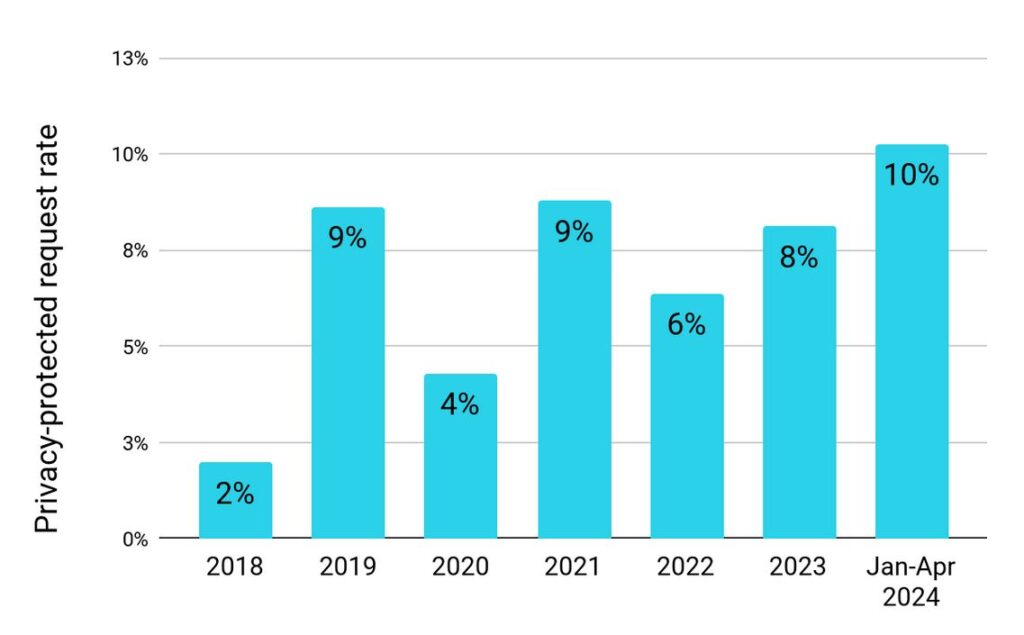

Prior to the implementation of RDRS, we tracked request rates for domains with Whois privacy (which we do not disclose through TACO) and, separately, request rates for domains with information already public in the Whois. RDRS has an outcome log option for “information is already public” and so we use that option when disclosure is requested both for a domain using our Whois privacy services (Contact Privacy for OpenSRS and Whois Privacy Protect for Enom) and when the registrant has already chosen to have their information public.

We have also created a new category in our tracking, “request withdrawn,” as this is an affirmative option in RDRS. We have had a few TACO requestors do this in the past; 1% of requests (2 total) fell into this new category.

Request outcomes, compared

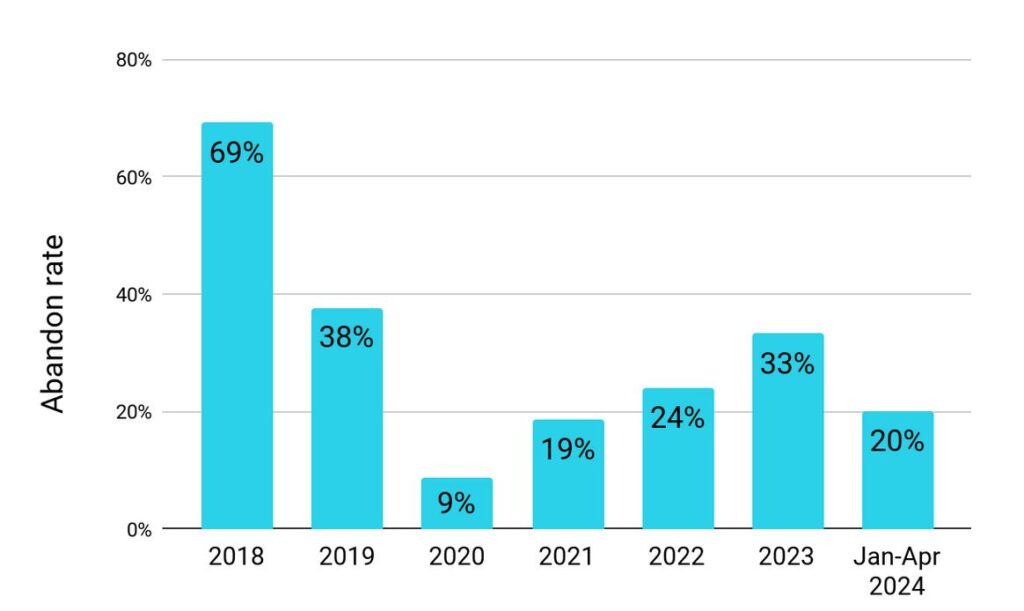

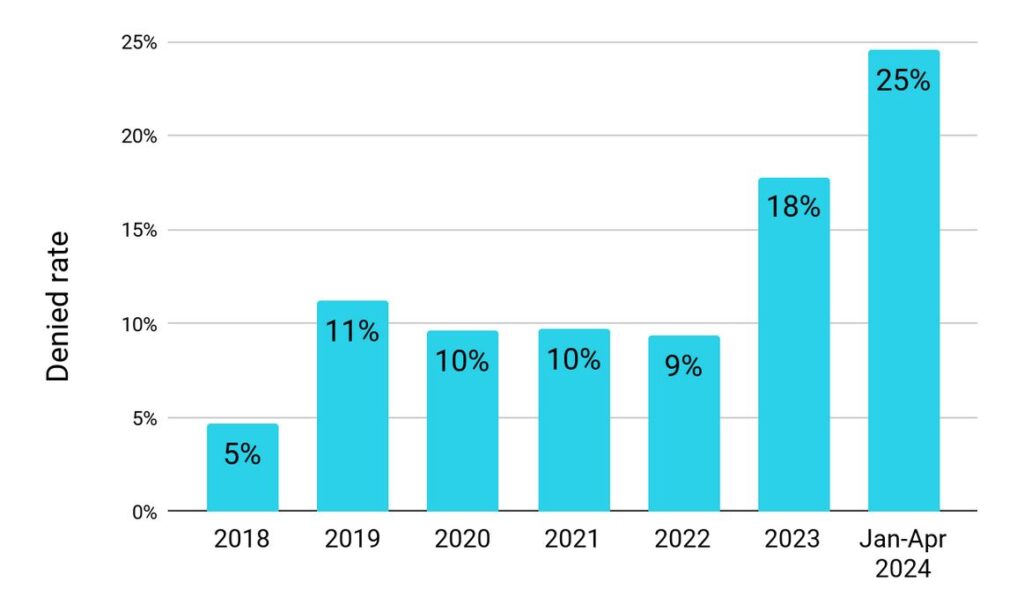

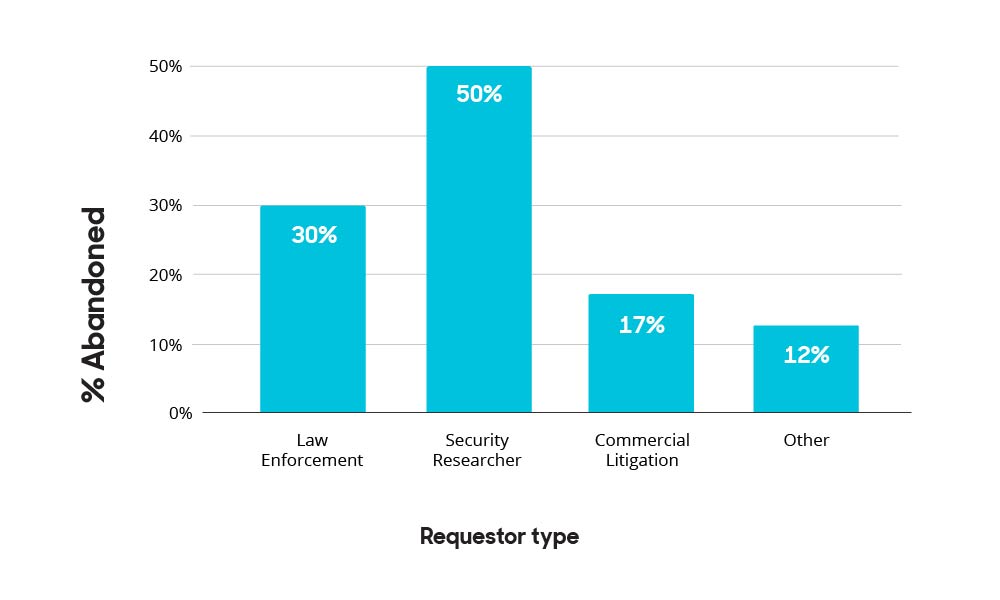

Looking at disclosure outcomes individually, the disclosure rate is up slightly compared to 2023’s total; the denial rate is also slightly higher. Abandoned requests have dropped to lower than we saw in 2023 or 2022, a trend we hope continues.

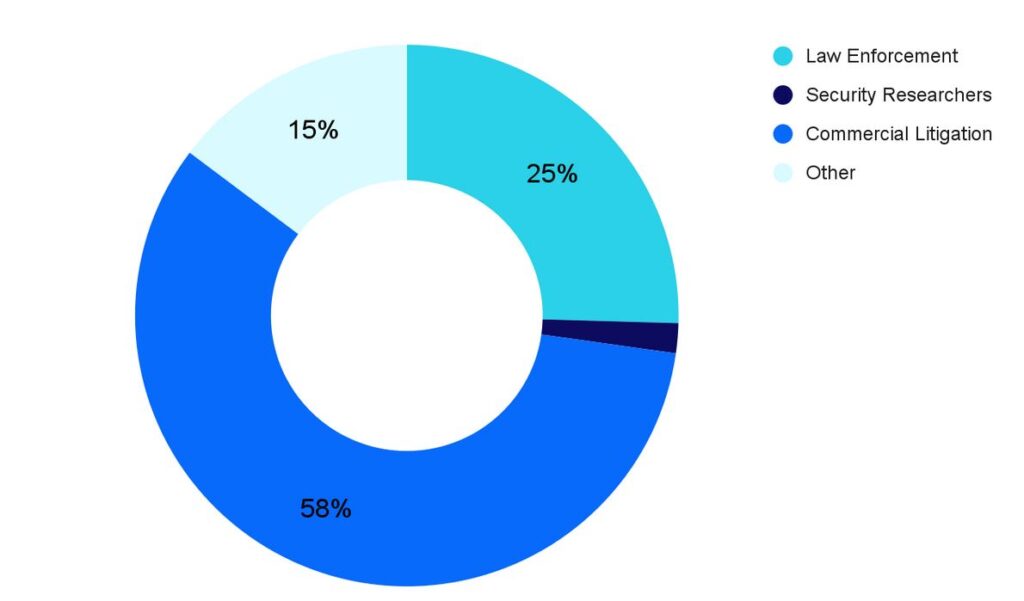

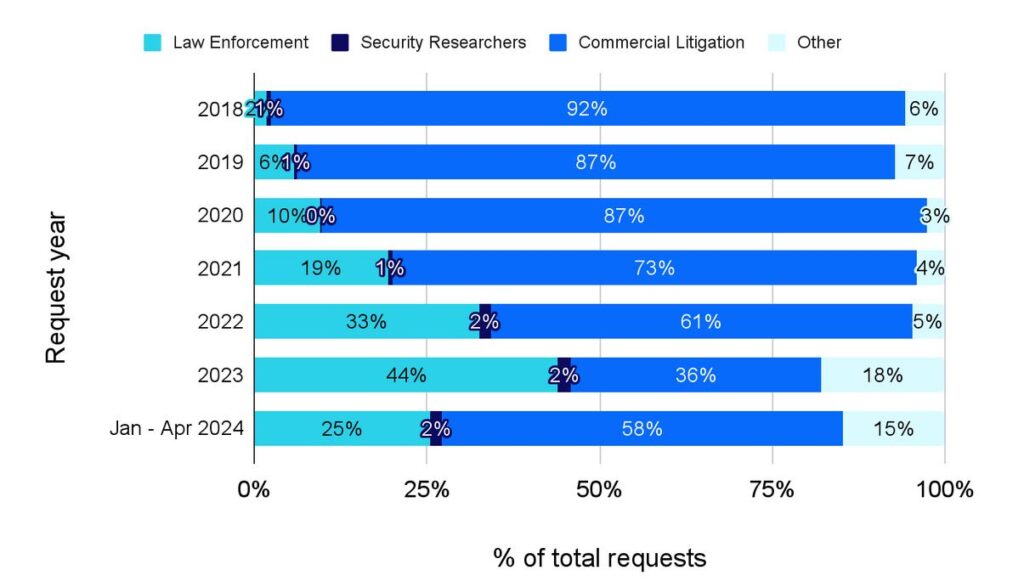

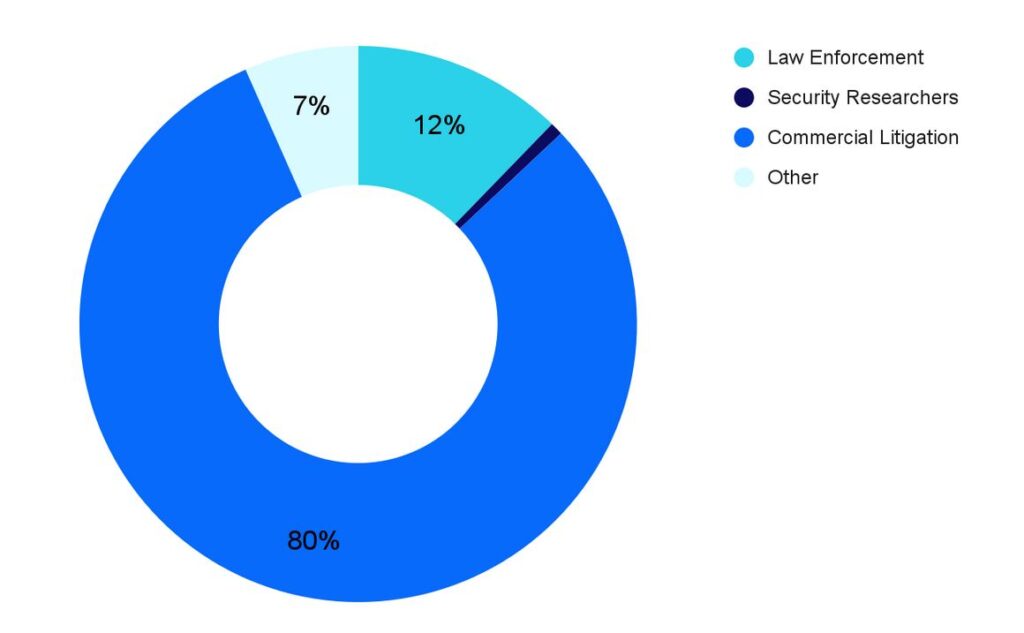

Requests by requestor category

Requests by category: new period (January – April 2024)

Despite our focus this time around on law enforcement, the bulk of our data disclosure requests continue to come from intellectual property lawyers. Law enforcement submitted half as many requests as IP lawyers did.

The “other” category covers a lot; common examples are:

- Domain owners who want to confirm what data they have on file or need help verifying their registration data

- Third parties that want to purchase the domain from the current owner or who want to use an email address at a domain that is already registered

- Individuals reporting abusive use of domains, often cryptocurrency scams

Requests by category since 2018

Requests by category (total)

Abandoned requests by requestor category (January – April 2024)

Total requests over time

To read our past Tiered Access blog posts, please see:

- OpenSRS’ Tiered Access Directory: a Look at the Numbers (May 2018 – mid-February 2019)

- Tiered Access Data Disclosure Update (mid-February – mid-October 2019)

- Privacy and Lawful Access to Personal Data at Tucows (mid-October 2019 – end of February 2020)

- Whois History and Updated Tiered Access Statistics (March – end of August 2020)

- Tiered Access request review process and updated statistics (September 2020 – end of August 2021)

- Tiered Access update: refreshed statistics and law enforcement processes (August – December 2021)

- Tiered Access update: registration data accuracy, and updated statistics (January – April 2022)

- Tiered Access update and thoughts on due process (May – August 2022)

- TACO platform updates

- Tiered Access update: policy check-in and updated statistics (September – December 2022)

- Tiered Access update: centralized system development, and updated statistics (January – April 2023)

- Tiered Access update: “urgent” disclosure requests and updated statistics (May – August 2023)

- Tiered Access update: RDRS first experiences and updated statistics (September – December 2023)