The Internet as we know it may be fairly new, but that short history doesn’t mean it’s not also filled with cycles and repetition.

Back in 2003, ICANN convened the Whois Task Force, intended to improve the ability of Whois services to contribute to the stability and security of the Internet while balancing the need to protect the privacy of the personal data involved. The Task Force’s goals of defining the purposes of Whois services overall—and of specific points of contact—as well as determining what data should be public and how to provide access as needed to nonpublic data, is remarkably similar to the work done in the EPDP, which was recently tasked with updating ICANN policy to adhere to the GDPR and other relevant privacy and data protection legislation while ensuring lawful disclosure of registration data where necessary.

In 2005, in that same Task Force, the RrSG proposed the creation of an “Operational Point of Contact” to help address a specific issue:

the amount of data that ICANN requires registrars to display in the Whois is facilitating all sorts of undesirable behaviours like renewal scams, data mining, phishing, identity theft, and so on.

The RrSG proposal was intended to enable contact with the relevant person responsible for the domain while also maintaining the privacy of personal data—again, similar to what the EPDP would later attempt—but other groups on the Task Force focused instead on limiting data protection to only a small subset of domain owners in order to retain as much access as possible.

The Final Task Force Report on Whois Services, from 2007, gained support from the registrar and registry stakeholder groups (RrSG) and the non-commercial stakeholder group but did not receive the business or intellectual property constituencies’ support. The policy development world seems stuck in a loop, with the EPDP’s final report likely fated to end identically, despite our hopes that the ICANN community will be able to break that cycle.

Abusive use of publicly available domain registration data, which RrSG members call out regularly, including in the early ‘00s and again in the EPDP, takes many different forms. Although it’s been some time since they’ve popped up in the news, those who follow the domain industry will know of Brandon Gray Internet Services, also known as NameJuice or Domain Registry of America. Their history of gathering Whois data to spam registrants with emails disguised as domain name renewal notices is well-documented1, as is the damage done to domain owners and other Internet users. Typical complaints centered around registrants not knowing who their domain provider is or why a domain has been transferred away from their preferred registrar, paying for services that were unnecessary or nonexistent, and inability to manage domains after the transfer was completed. This began early in our Internet history when domain owners were less experienced in managing services and had fewer data privacy and protection rights—or at least lower awareness around how to exercise those rights. In recent years, NameJuice has managed to stay under the radar, carefully crafting its solicitations to remain within the bounds of “marketing” and to avoid legal and compliance action.

Abusive use of domain registration data took the form of bulk scraping of publicly available data from the Whois system; this data was then packaged and sold by enterprising cybercriminals to both security researchers with valid purpose and those seeking to use it for purely commercial purposes. Because security researchers benefited from this arrangement, they kept their heads in the sand about the accumulation of the data—one of the first instances of cybercrime tools for hire.

When unrestricted access to Whois data was terminated in May 2018, these data aggregators continued to sell previously collected data. This mass processing of historic and ongoing registration data is illegal. Even data that is public may only be processed in a manner compliant with data protection regulations, including the GDPR; this means that the organization doing the processing must have a legal basis to do so and make sure the data subject (the registrant) is fully informed.

Scraping is specifically prohibited in registrars’ terms of service for Whois data, yet security researchers, commercial litigators, and other parties seem eager to use such illicitly-obtained personal data while continuing to fight for access to information that was obtained through cybercrime.

Tucows is not blameless; we should have more aggressively prosecuted these “WhoWas” service providers2 while they were at the peak of their scraping and selling of this data, instead of merely implementing technical means to attempt to prevent their criminal activity (including rate limiting and requiring CAPTCHAs for lookups). While we did send cease and desist letters on multiple occasions, when these were ignored we did not take any additional action. We regret not having done so, especially as these companies continue to sell access to customers’ personal data to their complicit clients.

At this point, since registration data is mostly redacted unless and until the domain owner decides to make it public, bulk gathering up of registration data is a decreasing concern but is still very much on our radar.

This history should be kept in mind when reviewing this or any of our prior blog posts3 discussing the reasonable disclosure of previously-public Whois data. It is within the context of this profligate access to and abuse of Whois data that the flood of access requests registrars have received must be understood.

Responses to denial requests

Recently, the rhetoric from professional data requestors has shifted toward allegations of incorrect denials. Since we began tracking requests over two years ago, Tucows has denied only 241 requests, or 7% of all requests. We do not count abandoned requests as denials, as others do. Since May 2018, 51% of all requests are abandoned following our reasonable requests for additional information; this rate has dropped with each period.

Most often, requests ask for all data we have, including information that was never publicly available and information that relevant courts have deemed to be illegal to share. When we respond to a request for “Registrant, Admin, Tech-C, Billing, and all other domains owned by the registrant”, we consider that to be a request for “previously-public Whois data”. Billing information would require a subpoena and reverse Whois lookups have never been a function of the Whois database, despite the criminal services discussed above.

Of those 241 denials, vanishingly few of them have been disputed by the requestor—the handful of times it has happened, when our Legal team discussed the concern with the requestor, the end result was no disclosure. This tells us that our request review process is working properly, allowing us to filter out invalid requests and ensure that only those requestors who actually demonstrate a legitimate need for the data and commit to handling it with appropriate protections are able to obtain personal data.

More complaints have been about the data we disclose being inaccurate. We do not specifically track this, but this type of response has been coming in often enough that we are working on providing an easy way of reporting a Whois inaccuracy to us—rather than having to report to ICANN to then convey to us. This will be available from within our TACO system, since only people with access to non-public personal data would be able to indicate that the information may be incorrect; this will include the standard process of suspension of the domain in the event of no response from the registrant within the ICANN-mandated time frame.

Recent tiered access statistics

The statistics provided below are for the period beginning 1 March 2020 and ending 31 August 2020 (Period 4).

Requests for data disclosure

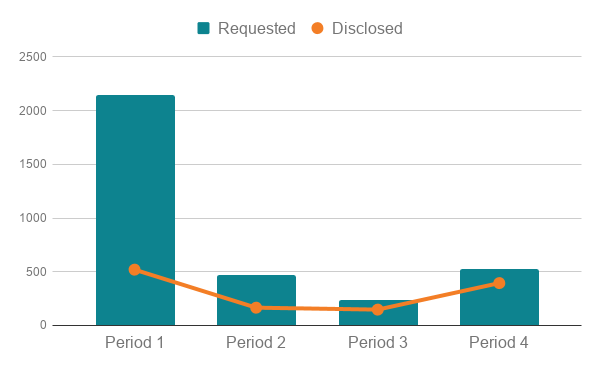

In Period 4, Tucows received 527 disclosure requests; our overall total since we began tracking this in May 2018 is 3,4004.

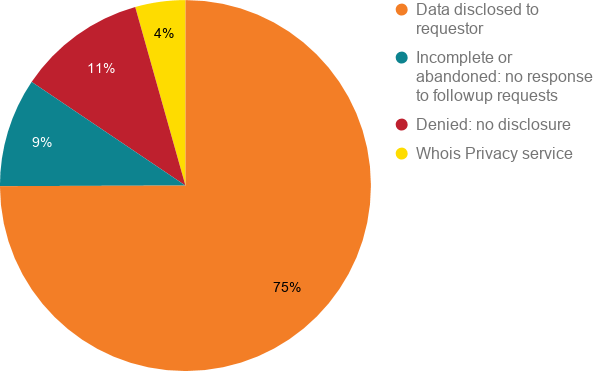

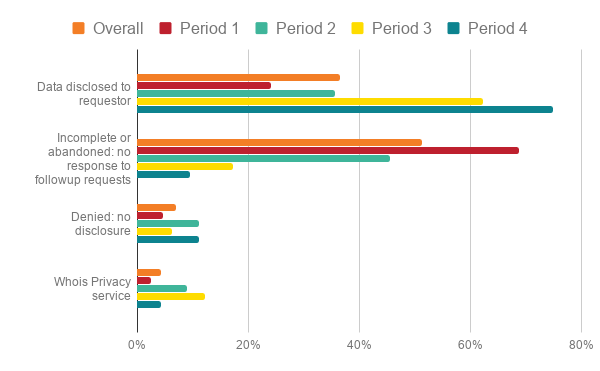

75% of requests resulted in the disclosure of domain registration data

This represents an increase of 13% compared to Period 3, which itself was double the rate of Period 2. As we discussed in the Period 3 report, this indicates improvement in the quality of the requests that we receive.

9% of requests were incomplete and, when we asked for additional information, the request was abandoned

This is a drop from the previous period and can likely be attributed to our ongoing outreach efforts and each requestor’s increasing familiarity with the process. We are beginning to see new requestors who already know to follow the RrSG-Recommended Minimum Required Information for a Whois Data Request. The part of the request most frequently missing is an assurance to only use the data for lawful purposes and to destroy the data after it is no longer needed.

11% of requests were denied, following a determination that the requestor did not have an adequate lawful basis

This remains concerningly high. Unlike abandoned requests, where asking for additional information results in the requestor deciding not to follow up with the request, denied requests represent a failure of the requestor to adequately evaluate the legal implications of their request. As discussed in our Privacy and Lawful Access to Personal Data blog post, the primary reason that requests get denied is that no human-reviewed the requests before they were submitted. The requests are for domains that may match all or part of a trademark but represent no threat to the mark for a variety of reasons. Our job is to balance the rights of the requestor—usually, an intellectual property owner or its representative—against the data protection and privacy rights of the registrant. Where a review of the domain—even the content hosted on it—results in confirmation that there is no danger to the mark, the balance favours privacy.

4% of requests were for domains with an active Whois Privacy service, so only the publicly available privacy service data were disclosed

While we are pleased to see this number reduced compared to the last period, we see some repeat requestors regularly asking for data they know to be behind one of our Whois Privacy services. This seems to be an attempt at “checking a legal box”: they are not asking for data they don’t know to be concealed, but rather, they are specifically not asking for the concealed data in the manner that they know will result in its disclosure, allowing them to indicate to their customers that they’ve gone through the process of requesting data but were “denied” without having to take the time and expense to file the actual paperwork that would result in its disclosure. We continue to reserve the right to blocklist requestors that regularly abuse our request process.

Requested vs. disclosed

As mentioned above, the increase in disclosure rates for this reporting period shows improvement in the quality of the requests that we receive.

Compared against previous reporting periods

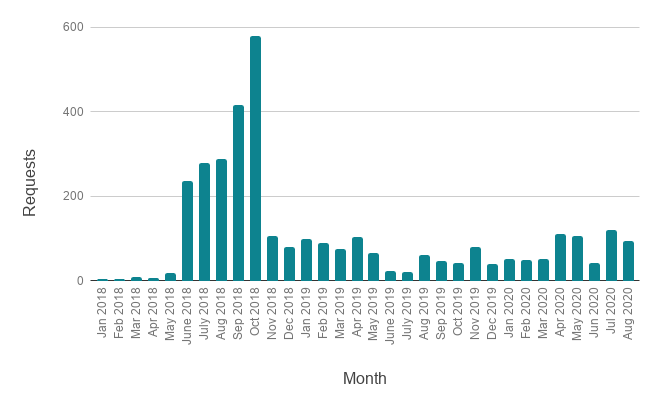

Requests over time

Here’s an illustration of the total volume of requests Tucows has received since the launch of our Tiered Access platform:

The number of requests appears to have stabilized, concurrent with the increase in quality of requests, a positive trend indicative of the industry as a whole settling into the new data protection landscape.

Disclosure request outcomes, compared

We are pleased to note that the rate of incomplete and abandoned requests continues to drop.

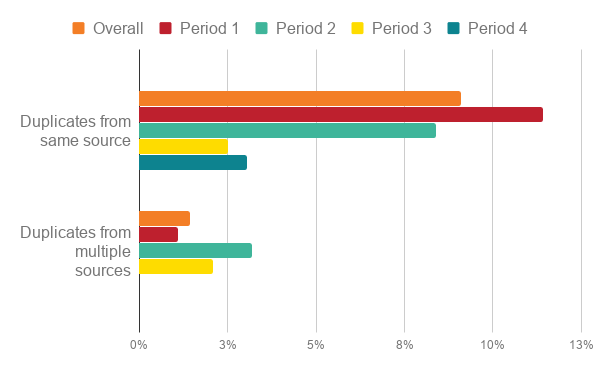

Duplicate requests

Duplicate requests have decreased, which we like to see, but an interesting new type of duplicative request that we have begun to see is that the owner of the intellectual property is reaching out to request data disclosure months or even years after the same data were already disclosed to a party claiming to be a representative of that owner. This is not tracked and currently remains rare but is an interesting insight into the relationships between professional data aggregators and the intellectual property owners they purport to represent.

Categories of requestors

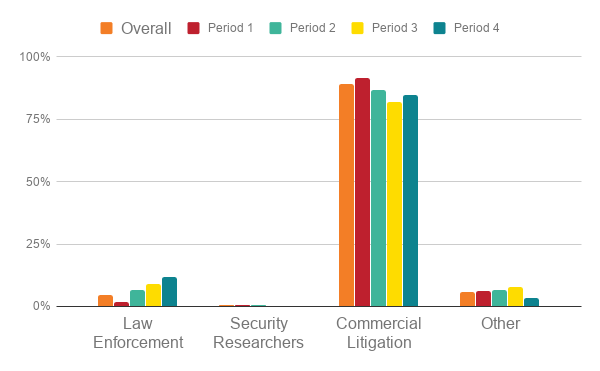

As readers of this blog series will know, we have grouped requestors into four main categories for tracking purposes. The main tracked requestor types are:

- commercial litigation, which requests disclosure of personal data in order to bring a legal claim of rights against the registrant;

- law enforcement, carrying out an investigation or otherwise in the course of their work;

- security researchers, who use certain aggregate data to identify trends in digital abuse; and

- other, which includes Certificate Authorities, resellers, private individuals, and sometimes even the registrants themselves.

At 84% of total requests, commercial litigation remains overwhelmingly the most frequent requestor type and, within that requestor type, professional data aggregators are the largest part. We are seeing a slight increase in Law Enforcement requests, up to 12% in Period 4.

We look forward to continuing to provide legally permissible access to non-public domain name registration data, including tracking the statistics for future review and insight into our industry.

1 Further reading:

- Brandon Gray Internet Services Inc. Litigation

- ICANN Notice of breach of registrar accreditation agreement

- ICANN Notice of suspension of registrar’s ability to create new registered names or initiate inbound transfers of registered names

- Ontario registrar stopped from selling dot ca domains

- Domain registry of America get slapped in UK

- ASA Adjudication on Domain Registry of America

2 DomainTools has the dubious distinction of being the most well-known of these PII-aggregators but is by no means the only. WhoisXMLAPI, who.is, and WHOXY also sell current and former personal data to their customers and, in some cases, operate an extortion scheme whereby a registrant can request exemption from this illegal sale.

3 You can find data for Period 1 in OpenSRS’ Tiered Access Directory: a Look at the Numbers, for Period 2 in Tiered Access Data Disclosure Update, and for Period 3 in Privacy and Lawful Access to Personal Data at Tucows.

4 “Total” numbers for a period may change after the period is reported because, although we have mostly successfully educated requestors about how to submit requests, we sometimes find requests that were misrouted—we deal with these when they are discovered but we count them as of the date of request, potentially changing numbers after we have reported them in a blog post. The impact is minor, so we do not feel the need to update prior posts but felt it prudent to indicate why the numbers might be slightly different if you’re comparing across posts.