Remember, although we have a great legal team working here at Tucows, none of what we share here can or should be taken as legal advice.

Among the world’s leading registrars, Tucows is the only one that has redacted all personal data from the public Whois and announced a data use consent management process for registrants worldwide. In making these changes, we’ve disrupted the status quo and encountered resistance from other industry members who would prefer a more conservative solution. But with our nearly two decades’ experience operating as an accredited domain registrar and supporting a large reseller network, we’ve learned that it is imperative to choose proactive solutions and remain focused on how the industry will develop long-term, rather than default to the most simple or convenient option.

We’ve said many times before that we believe individuals around the world have a right to the privacy and protection of their personal data. We’ve also made the more practical argument that while the GDPR may apply only to EU-local individuals, other governments have also passed data protection laws, and we expect more to follow suit. Today, we want to talk about why we remain confident in our approach and place it within the necessary context of worldwide data privacy regulations.

Comparing regional privacy laws

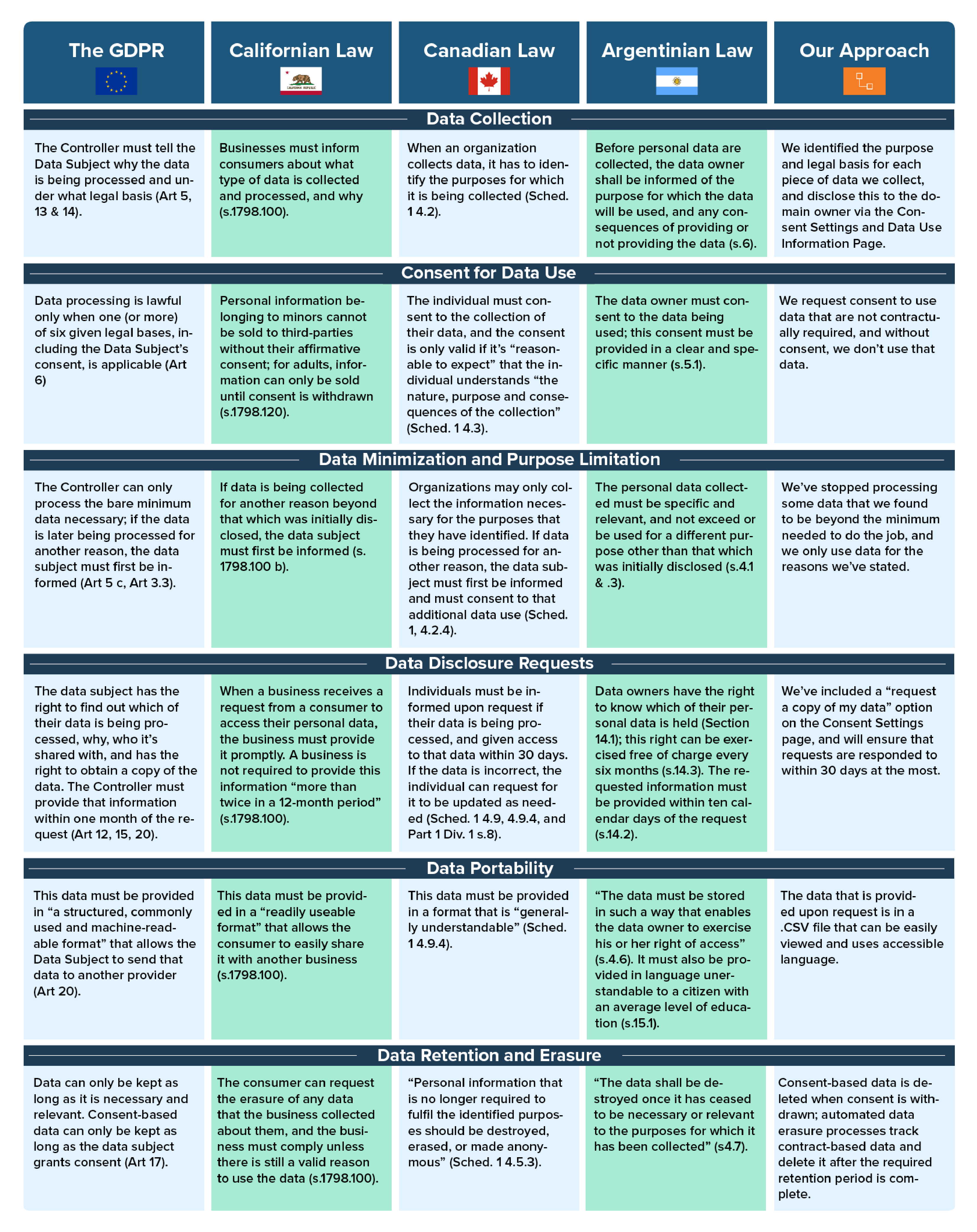

The GDPR has received a lot of attention not because it’s the only law of its kind, but because of its wide scope of applicability and, perhaps first and foremost, the severity of the penalties for non-compliance. There are other, less well-known laws in countries outside of the EU that establish similar data privacy protections. We’ve looked at a few important examples—Canada’s PIPEDA, California’s new Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, and the 2000 Argentina Personal Data Protection Act—to see how they stack up against the GDPR. You can jump to our summary table, which compares their fundamental concepts and relates them back to OpenSRS’ data-processing practices, or continue on below for a high-level overview of each law.

California

The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (AB 375) was signed into law by the state’s Governor on June 29, 2018. This new legislation takes effect in 2020, and many of the protections it extends to Californians will sound familiar to anyone who’s read up on the GDPR. At a high level, the CCP Act aims to ensure:

- The right of Californians to know what personal information is being collected about them.

- The right of Californians to know whether their personal information is sold or disclosed and to whom.

- The right of Californians to say no to the sale of personal information.

- The right of Californians to access their personal information.

- The right of Californians to equal service and price, even if they exercise their privacy rights (s.2.i).

The CCP Act has an interesting fundamental difference to the GDPR: the GDPR protects the data, while the CCP Act protects the consumer. The GDPR sets out rights and obligations for Data Controllers, Data Processors, and Data Subjects, while the CCP Act focuses on the rights a consumer has in relation to businesses that process their data. Even with this scope of applicability in mind, it’s very clear that we can expect to see a heightened level of transparency and consumer control over data in California.

These rights under the California Consumer Privacy Act will, of course, be subject to limitations, and the finer details will no doubt shift as government officials and private interest groups work to tighten up data privacy practices in a way that is not detrimental to the Californian businesses that rely on consumer data, including tech giants like Google and Facebook.

It’s both fitting and encouraging that California, a hub for technological innovation, is leading the U.S. movement to protect individual privacy in our digital age. And while there may not be policy in development at the federal level just yet, other American states are well on their way to passing modernized data privacy legislation—check out this handy, albeit, slightly outdated, map for more details. It seems likely that some of the important provisions in California’s Consumer Privacy Act will serve as a template for other state governments looking to establish stricter data privacy laws.

Canada

Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) has been in place since 2000, but an accompanying document, “Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent,” was just released in its final form on May 24, 2018, shortly before the GDPR came into effect. PIPEDA shares a number of similarities with the GDPR, which these new guidelines serve to highlight.

PIPEDA may not explicitly mention “data minimization,” but it does state that “an organization may collect, use or disclose personal information only for purposes that a reasonable person would consider are appropriate in the circumstances” (Division 1.3). This idea is echoed and expanded in later sections, including “Principle 5 — Limiting Use, Disclosure, and Retention,” which declares that data “shall not be used or disclosed for purposes other than those for which it was collected, except with the consent of the individual or as required by law.” Much like the GDPR, PIPEDA has a clear aim to curb deceitful or indiscriminate data collection.

In addition to restricting what data is processed, PIPEDA also calls for a high level of transparency around how and why data is processed. Its “Openness” principle affords individuals the right to request information about an organization’s data processing policies and practices, such as “a description of the type of personal information held by the organization, including a general account of its use” (Sched. 1 4.8.2). PIPEDA also requires organizations to obtain an individual’s consent before processing personal data, and specifies that this consent is “only valid if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting” (Div.1, 6.1).

Does this allow for service providers to bury the “nature, purpose and consequences” in the fine print? The word “reasonable” always invites a high degree of subjectivity. But the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (the “OPC”) released a related document, “Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent,” which addresses any confusion. It states that “in order for an organization to demonstrate that it has obtained valid consent, pointing to a line buried in a privacy policy will not suffice.” Pretty clear.

These Guidelines (well-summarized here) also put forth an idea quite reminiscent of the GDPR’s distinction between the legal bases of consent and contract. In Canada, individuals must be offered a clear “yes or no” option to consent to data processing. However, an exception to this rule is the collection or disclosure of personal information that’s required, or to quote directly, “integral to the product or service.” The collection or disclosure of such essential data are referred to as “conditions of service,” and can’t be opted out of without opting not to use the service at all. This is very similar to how contract-based data, those data elements which are required in order to provide the service for which they are collected, do not require explicit consent under the GDPR.

The OPC also acknowledges that while some individuals may be content with a quick overview of what personal data is being collected, others will want a greater level of detail about their provider’s privacy and data use practices before making a consent choice. Organizations are encouraged to meet the needs of all users by presenting information in a “layered-format”, or some other method that provides the user with control “over how much detail is provided to them.” Our consent management process embodies this idea. We’ve clearly outlined the how, what, and why of our data collection practices, in a manner that avoids bombarding the reader with inaccessible legalese. Those looking to dive deeper can review our Data Use Information page, which we’ve also designed to be accessible to the average reader.

Argentina

Argentina’s Personal Data Protection Act is also an older data protection law, in effect since 2000. Argentina was the first Latin American nation designated by the EU as having an “adequate level of data protection” as compared to EU requirements.

Argentina’s Data Protection Act is easily comparable to the GDPR, particularly in regard to the latter’s data minimization principle and distinctive treatment of consent- and contract-based data. The Argentine law requires that data collected must be “certain, appropriate, pertinent, and not excessive with reference to the scope within and purpose for which such data were secured” (Chapter 2, s.4.1). In addition to restricting what data can be collected, the Act also states that data must only be kept while it is necessary and relevant to the purposes for which it was initially collected—if it ceases to fulfill these requirements, it must be “destroyed” (s.4.4.7).

These obligations go hand-in-hand with consent requirements: data processing is not permitted without the consent of the individual whose data is being processed, except in certain defined circumstances. The most notable exception to this requirement is the processing of data that arises “from a contractual relationship,” and which is necessary to develop or fulfill that contract. Here again, the consent request cannot be buried in the fine print. It must appear in a “prominent and express manner” (s.5.1).

Argentina is currently working to create updated data protection regulations, which will be “heavily based upon the GDPR.” Thus far, we’ve only been able to locate a Spanish-language version of the updated draft bill, so we are relying on secondary sources for insight into how it compares to its EU equivalent. In a 2017 IAPP article, GDPR matchup: Argentina’s draft Data Protection Act, Pablo A. Palazzi and Andres Chomczyk provide a solid overview of the changes being made in an effort to bring the Argentine Law in line with the EU Regulation. Their review of the draft bill notes the introduction of “new legal bases” for data processing, including, “legitimate interest,” and the addition of “sections on child consent, data breaches, accountability, privacy by design, the duty to have a data protection officer and mandatory impact studies,” all of which closely resemble the GDPR’s data protection methods.

It seems we can expect the updated Argentine law to mirror many of the GDPR’s fundamental components and, according to Palazzi and Chomczyk, even its scope of applicability; the draft outlines “new ways to determine whether an entity or certain data processing is subject to Argentine Law, quite similar to the criteria found in the GDPR.”

We’re eager to view the new law in its final form and learn when it will take effect. The law in place at this time already includes many safeguards to ensure a high level of transparency and individual control around data collection, so in some ways, we don’t expect anything truly surprising from its successor, especially if the new version does indeed follow closely the GDPR. Our GDPR implementation efforts will likely prove sufficient to meet any updated Argentine requirements as well.

Evolving global data privacy standards

The policy revision efforts underway in Argentina speak to the GDPR’s global impact. Not only do the Regulation’s data processing requirements apply to organizations outside the EU that process the data of EU locals, the GDPR also serves as a standard, perhaps particularly for countries who wish to maintain or establish adequacy status with the EU.

Just before this blog post went to “print,” India took a major step toward data privacy reform with the release of a report, “A Free and Fair Digital Economy Protecting Privacy, Empowering Indians,” that’s to serve as a draft data protection bill. In a recent Data Protection Committee press conference, Ravi Shankar Prasad, Union Minister for Law and Justice & Information Technology, Government of India, noted that India’s Supreme Court “would like Indian’s data protection law to become some kind of model for the…world…” (4m20s).

For those interested, France’s Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés maintains a global map existing privacy law (check it out!), which may look quite different even five years from now.

A comparison of data privacy laws and OpenSRS’ GDPR changes

To contextualize our recent changes in relation to the GDPR, California’s Consumer Privacy Act, Canada’s PIPEDA, and Argentina’s Personal Data Protection Act, we’ve put together this comparison chart. As you’ll see, many of the core concepts remain the same across borders. This confirms our position that our recent updates demonstrate a proportionate and forward-thinking approach to the rapidly-shifting landscape of global data privacy regulation.

Reflecting on our GDPR changes

We could have applied our GDPR processes to EU-locals only, allowing resellers who don’t offer services to clients in the EU to proceed with business as usual, unconcerned with the GDPR. But that solution would not only have put our resellers and us at risk of improperly processing the personal data of EU-local individuals, it was also not a viable long-term option. Data privacy standards around the world are evolving and not in a direction that supports the unnecessary collection of personal data or the continued display of unredacted personal data in the public Whois directory without the data subject’s clear and specific consent. If the laws we reviewed today are any indication of where things are headed, OpenSRS and our reseller partners can feel confident that our GDPR implementation work has positioned us all to meet and adapt to changing data privacy requirements.

Our decision to redact data from the public Whois, even before ICANN confirmed this as an appropriate response to the GDPR, was part of larger move towards a gated Whois solution. In designing our “Tiered Access Directory”, we’ve done our best to balance individual privacy and the rights of registrants with those of law enforcement and other community members. Our consent management process establishes a high level of transparency about what data we collect and why and provides registrants an easy means of revoking consent and submitting data use disclosure requests. These changes may cause some friction in the short term but we are confident they will help us meet the long-term needs of our resellers and ensure we’re protecting their businesses as well as our own.

On a less practical note, our parent company, Tucows, maintains a long-time commitment to “lobby, agitate, and educate to promote and protect an open Internet around the world.” Part of ensuring that the Internet remains free and open is ensuring that basic individual rights, including control over one’s personal information, continue to be protected as personal data becomes more ubiquitous and easy to share than ever before. The laws we’ve looked at here take varied approaches to addressing this challenge but also share some important similarities and reflect values that are becoming more and more universal: greater transparency on the part of organizations and greater control for individuals.

Want to learn more?

ICANN has been tracking global data privacy regulations and published their second report on August 30. This review highlights laws around the world that could have an effect on online businesses.